On Knowable Objects

On Knowable Objects

From The Unmistaken Commentary on the Intention of the Seven Treatises [of Dharmakīrti] and the Sūtra [i.e., the Pramāṇasamuccaya of Dignāga]—Clarifying the Meaning of Sakya Paṇḍita's Treasury of Valid Reasoning

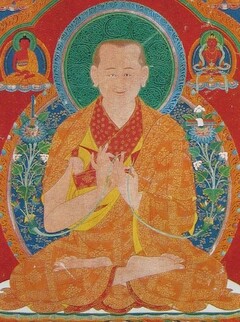

by Gorampa Sonam Senge

The Definition

The definition of an object (yul) is that which can be known by the mind.

This has equal pervasion with: 1) a knowable object (shes bya), defined as “that which can be taken as an object by the mind”; 2) an object of comprehension (gzhal bya), defined as “that which can be comprehended by valid cognition”; 3) an established base (gzhi grub), defined as “the observed object of a valid cognition”; 4) a definite existent (yod nges), defined as “that which can be observed by a valid cognition”.

[...]

A. A Division into Four Types, Based on How They Function as an Object

1. Analysis of Which Phenomena Become the Four Kinds of Objects

All phenomena become the three types of objects, namely appearing object (snang yul), referent object (zhen yul) and object of engagement ('jug yul), depending on their individual subject, the mind. [On top of those], for the Sūtra Followers, the apprehended object (gzung yul) corresponds exclusively to the five outer sense sources.[1] In the system of the Mind-Only School there is no presentation of an apprehended object.

2. Analysis of which objects exist for each type of subject

All non-mistaken, non-conceptual consciousnesses have an appearing object. Mistaken non-conceptual consciousnesses do not have one. All conceptual [consciousness] have an appearing object.

As for the apprehended object, only the two kinds of direct perception within object-awareness[2] have one.

Factually concordant[3] conceptual cognitions have a referent object.

Objects of engagement exist for: 1) valid cognitions; 2) factually concordant sounds that are means of expression,[4] and 3) persons.

3. The Respective Natures of Each of the Four Objects

a) The Appearing Object

a.1) Definition

An appearing object is any object that appears, either by casting its own aspect, or directly without an aspect.

a.2) Divisions

For the appearing object of a non-conceptual consciousness, those [appearing objects] that appear by casting an aspect correspond to the realities[5] apprehended by a direct perception of object-awareness,[6] whereas those that appear without casting an aspect correspond to what is experienced in a direct perception of self-awareness.

The appearing object of a conceptual [consciousness] is an object generality (spyi don).

Alternatively, the appearing object, as a subdivision of the four types of objects, is not different in substance with the consciousness that is the subject.

For the presentation of what appears at the same time, only three are given: 1. what is experienced by a direct perception of self-awareness, 2. the non-existent clear appearance that actually appears to a non-conceptual wrong consciousness, and 3. the object generality that actually appears to a conceptual [consciousness].

As for the second of these [i.e., the non-existent clear appearance], I think that the intended meaning of the Treasury of Valid Reasoning is that it is the appearing object of the consciousness, but it is not generally [considered] to be an appearing object. [This is how I] analyse this.

b) The Apprehended Object

The definition the apprehended object is: the outer object that actually casts an aspect similar to itself upon the direct perception that apprehends it.

When subdivided in terms of the subject, there are 1) the apprehended objects of direct sense perception, and 2) those of direct mental perception. In terms of the object, there are five: forms, sounds, smells, tastes and textures.

c) The Referent Object

The definition of the referent object is: that of which one becomes aware, when the mind’s mode of apprehension refers[7] to it by making it its principal focus.

These are divided into two [types]: the referent object of a conceptual valid cognition, and the referent object of a determinate cognition.[8] The first is the [same as] the object of engagement of a valid inference. For the second, the very same objects of engagement of the two types of valid cognition [i.e., direct perception and inference] become the referent objects of the determinate cognitions [subsequently] induced by those.

c) The Object of Engagement

The object of engagement is the main object that is the basis for a factually concordant subject[9] to engage in an action.

When divided in terms of the subject, as we have already seen, there are three.[10]

First, the objects of engagement of valid cognitions are of two types: those of direct perception and those of inference.

For direct perception, the object of engagement of a direct perception of object-awareness[11] is the specifically characterized outer object. The object of engagement of a direct perception of self-awareness is the specifically characterized consciousness. For the Sūtra Followers, the object of engagement of a yogic direct perception is the specifically characterized aggregates qualified by selflessness,[12] whereas for the Cognitive Awareness School[13] it is the nature of reality (dharmatā) itself.

The object of engagement of an inference is classified as the proposition proven by a valid reason.[14]

Second, there is the object of engagement of a sound. For example, the object of engagement of the factually concordant sound “cow” is that specifically characterized cow.

[The object of engagement of a person is not explained.]

B. Division into Two Truths in Terms of Their Natures

For the Particularist School, the definition of conventional truth is: that which, when it is [physically] destroyed or mentally dissected, is no longer engaged in by the apprehending mind. For example, when a vase is destroyed, the mind that would apprehend it can no longer engage with it. And in the case of water, as is known to the world, if it is dissected by the mind into the eight constituents of matter,[15] the mind that would apprehend [this water] no can no longer engage with it.

The definition of ultimate truth is: that which can still be engaged in by the mind that apprehends it, even if it is [physically] destroyed or mentally dissected, as in the example of the form sense-source.[16]

As the Treasury of Abhidharma says:

Things which, when destroyed or mentally dissected,

Can no longer be identified by the mind,

Such as pots or water, are relative.

All else besides is ultimately existent.[17]

For the Sūtra Followers, the definitions of ultimate and conventional truth are, respectively, those phenomena that are ultimately capable or incapable of performing a function, as indicated by the statement: “the ultimate is that which can perform a function”.

For the Mind-Only School, the definition of conventional truth is: that which makes thorough affliction[18] increase when one actually focuses on it; and the definition of ultimate truth is: that which is pervaded by the increase of complete purification[19] when one actually focuses on it.

As it is taught in the Compendium [of Abhidharma]: “If, when one focuses on a certain object, thorough affliction proliferates, that object of focus exists conventionally. If, by focusing on a certain object, complete purification grows, that object of focus exists ultimately.”

For the Middle Way School, the definition of ultimate truth is: that which is grasped by a mode of apprehension that sees authentically, such as what is grasped by the mode of apprehension of a noble being in meditative equipoise. And the definition of conventional truth is: that which is grasped by a mode of apprehension that sees conventionally, such as the actual object of the mind of an ordinary individual.

As it is taught in the Introduction to the Middle Way: “For all things two natures are apprehended: one found through seeing their reality, and another found through seeing their deceptive character. The object of the mind that sees reality is suchness [i.e., ultimate truth], and that of the mind that sees deceptive entities is conventional truth.”[20]

C. Division into Manifest and Concealed, in Terms of the Object of Engagement

1. Definitions

The definition [of a manifest object] is: that which is truly known without depending on an object generality; and the definition [of a concealed object] is: that which is truly known by means of an object generality.

2. Divisions

a. Manifest Objects

Manifest [objects] are divided in terms of the object into 1) the phenomenal object (chos can), and 2) its intrinsic nature (chos nyid). Phenomenal objects in turn are divided into [material] things and consciousness.

In terms of the subject, they are divided into those [cognized] by a non-conceptual, non-mistaken consciousness, and those [cognized] by a non-conceptual mistaken consciousness.

For [the non-mistaken case], 1) the manifest objects of direct perception of object-awareness are the five objects [of the senses], such as form); 2) the manifest objects of direct perception of self-awareness are all consciousnesses; and 3) the manifest object of yogic direct perception is the nature of reality (dharmatā).

[For mistaken minds], there are such things as the two moons that are the manifest [object] of a sense consciousness perceiving two moons.

b. Concealed Objects

Concealed [objects] are divided in terms of the object, as before, into such things as 1) a vase, which is concealed with respect to the conceptual [mind] that apprehends ‘vase’; 2) the consciousness in one’s own continuum, which is concealed with respect to the mind of another person who is not clairvoyant; and 3) the nature of reality, which is concealed for ordinary individuals.

In terms of the subject, concealed objects are divided into [those cognized by] inferences and [those cognized by] invalid [conceptual] minds.

For inferences, there are three types of concealed objects that are proved by the logical arguments of 1) inference by the power of facts, 2) inference based on trust (yid ches), and 3) inference from what is commonly accepted.

For [invalid conceptual minds], there are the concealed objects of 1) determinate cognitions, such as the [actual] blue which is concealed with respect to the ascertaining consciousness induced by the sense direct perception apprehending [the colour] blue; 2) wrong consciousness, such as the permanent sound which is concealed for the conceptual mind that apprehends ‘permanent sound’; and in the case of 3) doubt, the fact of sound actually being permanent or impermanent (as the case may be) [is concealed] with respect to the manifest doubt of the individual who harbours it.

Therefore, whatever is a manifest [object] of non-conceptual wrong consciousness is not necessarily pervaded by being a manifest [object], and whatever is a concealed [object] of a wrong conceptual consciousness is not necessarily pervaded by being a concealed [object]. The reason for that is that the appearing object of a non-conceptual wrong consciousness is not necessarily an existing [entity], and the same goes for the referent object of a conceptual wrong consciousness.

In the case of doubt, the position that accords with reality is a concealed [object], but the other one is not.

D. Division into Specifically and Generally [Characterized Objects], in Terms of the Mode of Engagement

1. Definitions

The definition [of a specifically characterized object] is: a thing (dngos po) that abides without any mixing in place, time or nature; and [the definition of a generally characterized object] is: a superimposition that appears as shared in terms of place, time or nature.

Alternatively, [they can be defined respectively] as “a thing that abides without being shared” and “a superimposition that appears as shared.” As the Ascertainment of Valid Cognition says: “as for the nature of a thing that abides without being shared, that is the specifically characterized”. These two [definitions] are known from this quotation, [the first] directly [and the second] indirectly.

2. Divisions

The specifically characterized are classified into two: [material] objects and consciousness. Material objects are the five outer sense sources (forms, [sounds, smells, tastes and textures]) as well as the five inner sense sources (the eye, [ear, nose, tongue and body]). Specifically characterized consciousness is divided into the six classes of consciousness together with their accompanying [mental events].

For the earlier Tibetan scholars, the generally characterized are classified into the two of 1) isolates that are a non-implicative negation, and 2) generalities that are an elimination-of-other done by a mind. However, in the authoritative text is it taught that there are three [types] of generalities: those that depend on things, those that depend on non-things, and those that depend on both, as shown by the statement: “since they depend on things, non-things, or both, there are three kinds of generalities”.[21]

Otherwise, generalities can also be divided into four types: 1) those that separate that which is singular into a multiplicity; 2) those that gather that which is multiple into something singular; 3) those to which the singular appears as singular; and 4) those to which the multiple appears as multiple.

Exclusions-of-other can be divided like this, because ‘generality’, ‘generally characterized’ and ‘exclusion-of-other’ share a single essential meaning.

E. Ultimately, All Objects of Comprehension Are Condensed into the Specifically Characterized Alone

Now, one may wonder what is the meaning of the teaching according to which the object of comprehension is the specifically characterized alone, as in the statement “the specifically characterized is the unique object of comprehension”.[22]

Generally speaking, in the textual tradition on logic, one first identifies the kind of valid cognition that is known to all, whether they engage in philosophical tenets or not. Then comes the point of proving that the Teacher [whose teaching is] similar to that [common valid cognition] is a completely valid person, as shown by the statements on recognizing [valid cognition] as “that which is non-deceiving and illuminates what was not known [before]”, up to “the Bhagavan who is endowed with that [valid cognition] is a valid [person]”.[23]

What is meant by the “valid cognition that is known to all, whether they engage in philosophical tenets or not”, is the cognition that becomes the cause for adopting objects that have the power to bring benefit, and rejecting those that bring harm. This is taught by the quotation from the Compendium of Valid Cognition: “Since securing what is beneficial and abandoning what is harmful are necessarily preceded by an authentic cognition...”[24]

Furthermore, the objects that have the power to bring benefit and are adopted through this valid cognition, and the objects that have the power to bring harm and are abandoned through this valid cognition, are specifically characterized objects alone, because only specifically characterized entities have the power to bring benefit or harm; the generally characterized do not. This is shown by the quotations “since they bring the results of adopting and abandoning, all beings engage in them,”[25] and “who would conceptually pursue that which is not causally effective?”.[26]

The specifically characterized alone is both the apprehended object when one’s assessment operates through direct perception of object-awareness, and the referent object when the assessment is done through inference. Also, since the individual is not deceived when they engage [with the object] on the basis of either of these two valid cognitions, [the specifically characterized object] is also the object of engagement.

Considering this point, the auto-commentary on the Treasury of Valid Cognition says: “When the specifically characterized is assessed directly, it is the apprehended object, and when it is assessed as a concealed [object], it is the referent object. But in both cases, since the individual who engages is not deceived, it is [also] the object of engagement.” Here, “being assessed directly” has the same meaning as “being assessed as a manifest [object]”, as we can know from the auxiliary word.[27]

In brief, regarding the specifically characterized alone, when one engages to assess it through the two valid cognitions of direct perception and inference, in terms of the mode of engagement there are two objects of comprehension—the specifically and the generally characterized. But in terms of the object of engagement there is only one object of comprehension: the specifically characterized. This is the unerring intention of [Dharmakīrti’s] statement: “the specifically characterized is the unique object of comprehension”.[28]

As Devendrabuddhi writes: “Since only the specifically characterized is truly known either through its own nature or through another nature, exactly two are posited: its own characteristics just as they are, and the object of comprehension.”[29]

| Translated by Roger Espel Llima, 2019. With thanks to Khenpo Chöying Dorje and Do Tulku Rinpoche for many clarifications, and to the Milinda project for sponsoring this translation.

Bibliography

Tibetan Edition Used

kun dga' rgyal mtshan. tshad ma rigs gter rtsa ba dang 'grel pa, pp. 104-114. si khron mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 1998. BDRC W20402

Other Primary Sources

Candrakīrti. Introduction to the Middle Way (Madhyamakāvatāra).

Devendrabuddhi. Elucidation of [Dharmakīrti’s] Commentary on Valid Cognition (Pramāṇavārttikapañjikā).

Dharmakīrti. Commentary on Valid Cognition (Pramāṇavarttika).

Dharmakīrti. Ascertainment of Valid Cognition (Pramāṇaviniścaya).

Jamyang Loter Wangpo ('jam dbyangs blo gter dbang po). The Lamp that Illuminates the Seven Treatises—A Word by Word Commentary on the Treasury of Valid Reasoning (tshad ma rigs pa'i gter gyi mchan 'grel sde bdun gsal ba'i sgron me), in tshad ma rigs gter rtsa ba dang 'grel pa, pp. 463 ff. si khron mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 1998. BDRC W20402

Vasubandhu. Treasury of Abhidharma (Abhidharmakośa).

Secondary Sources

Bimal Krishna Matilal. Epistemology, Logic and Grammar in Indian Philosophical Analysis. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Dreyfus, George B. J. Recognizing Reality—Dharmakirti's Philosophy and its Tibetan Interpretations. State University of New York Press, 1997.

Dunne, John D. Foundations of Dharmakīrti's Philosophy. Wisdom Publications, 2004.

Gold, Jonathan C. Sakya Paṇḍita's Anti-Realism as a Return to Mainstream in Philosophy East and West, Vol. 64, No. 2 (April 2014), pp. 360-374.

Hugon, Pascale. Is Dharmakīrti Grabbing the Rabbit by the Horns? A Reassessment of the Scope of Prameya in Dharmakīrtian Epistemology in Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 39, No. 4/5 (October 2011), pp. 367-389

Hugon, Pascale. Trésors du Raisonnement—Sa skya Paṇḍita et ses prédécesseurs tibétains sur les modes de fonctionnement de la pensée et les fondements de l'inférence. Arbeitskreis für Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien, 2008.

Kapstein, Matthew. The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism, pp. 89-96. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Moriyama, Shinya. Omniscience and Religious Authority: 4: A Study on Prajñākaragupta's Pramāṇavārttikālaṅkārabhāṣya and Pramāṇavārttika II 8-10 and 29-33 Lit Verlag, 2014.

Przybyslawski, Arthur. Cognizable Object in Tshad ma rigs gter According to Go rams pa in Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 44, No. 5 (November 2016), pp. 957-991.

Stolz, Jonathan. Sakya Pandita and the Status of Concepts in Philosophy East and West, Vol. 56, No. 4 (October 2006), pp. 567-582.

Van der Kuijp, Leonard. Phya-pa chos kyi seng ge's Impact on Tibetan Epistemological Theory in Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 4, No. 3-4 (September 1977), pp. 355-369.

Version: 1.3-20221118

-

Tib. skye mched; Skt. āyatana; sometimes also translated as “spheres”. ↩

-

Tib. don rig. These two types are direct sense perception of outer objects, and direct mental perception. ↩

-

Tib. don mthun, i.e., that accords with reality. ↩

-

i.e., expressed sounds that correspond to an actual outer object, as with the words “this pot”. ↩

-

Tib. don; often also translated as “object”, but here we must distinguish it from yul. ↩

-

i.e., a direct perception of an outer object. ↩

-

Tib. zhen pa; the general meaning of the verb is “to cling”; the same word is used in a technical sense in the field of Pramāṇa with the sense of “reference”. ↩

-

See the Treasury of Valid Reasoning, Chapter 2, for the definition of a “determinate cognition” (Tib. bcad shes) in the system of Chapa Chökyi Senge (phywa pa chos kyi seng ge), and its refutation as a separate category by Sakya Paṇḍita. ↩

-

i.e., of a factually concordant mind. ↩

-

As above: belonging to valid cognitions, sounds that accord with reality, and persons. ↩

-

i.e., the perception of an outer object ↩

-

Reading bdag med pa for bag med pa. ↩

-

Tib. rnam rig pa, Skt. Vijñapti[mātratā]vāda, meaning “those who assert cognitive awareness [only]”, here identified with the Mind-Only school. ↩

-

Such as the existence on the smoky hill of a fire, whose burning heat you can physically engage with. ↩

-

The four elements (earth, water, fire, wind) and the four stable sensibilia (form, smell, taste and physical texture), that together make the eight types of ultimate partless particle for the Particularist School. ↩

-

Tib. gzugs kyi skye mched. Presumably referring to the smallest perceptible elements of outer form. ↩

-

Treasury of Abhidharma (Abhidharmakośa), VI, 4. ↩

-

Tib. kun nas nyon mongs pa, Skt. saṃkleśa. This refers not only to the emotional afflictions themselves, but to the whole category of cyclic existence. ↩

-

Tib. rnam par byang ba, Skt. vyavadāna. This refers to all phenomena belonging to the category of nirvāṇa (including the path that leads to it). ↩

-

Candrakīrti, Madhyamakāvatāra, VI, 23. Translation from Geshe Rabten (1983). ↩

-

According to Pascale Hugon in Is Dharmakīrti grabbing the rabbit by the horns? (p. 374, footnote 27), “this last category does not imply that there are instances that both exist and do not exist, but that instances of this category can be either existent or non-existent.” The generality ‘object of knowledge’ would be such an example. ↩

-

From Dharmakīrti’s Commentary on Valid Cognition (Skt. Pramāṇavarttika), III.53d. ↩

-

The second quotation is from Commentary on Valid Cognition, II.7a. In Omniscience and Religious Authority by Shinya Moriyama (p. 23, footnote 30) this is further explained as: “Since just as perception and inference are means of valid cognition, so the Buddha who has the nature of wisdom also does not belie; the Buddha is nothing other than a means of valid cognition, [namely] perception as the self determination.” ↩

-

Identified as Ascertainment of Valid Cognition 1.152.3 by Arthur Przybyslawski. ↩

-

Identified as Ascertainment of Valid Cognition 1.173.4 by Arthur Przybyslawski. ↩

-

Identified by Arthur Przybyslawski as Commentary on Valid Cognition, I.211.ab. Translated there as “Why to pursue and investigate the object that is not effective”. ↩

-

Tib. tshig grogs, here referring to the adverbs “manifestly” (Tib. mngon gyur du) and “directly” (Tib. dngos su). ↩

-

Commentary on Valid Cognition (Skt. Pramāṇavarttika), III.53d. ↩

-

From Devendrabuddhi’s Elucidation of [Dharmakīrti’s] Commentary on Valid Cognition, p. 146A in http://tibetan.works/etext/reader.php?collection=tengyur&index=4217. Presumably the meaning is that the same single specifically characterized object is known directly by apprehending its own characteristics in the case of direct perception, and is known indirectly through inference, in which case it is called the object of comprehension. ↩