Introduction to Scholasticism in Tibetan Buddhism

Introduction to Scholasticism in Tibetan Buddhism

by Nicholas S. Hobhouse

The term ‘scholasticism’ originally referred to a form of theological thought and presentation that gained prominence in Catholic institutions in medieval Europe. However, it is now widely used in academic circles when discussing analogous activities in other religions, including the intellectual education in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. Although more detailed explanations can be found in the literature listed below, a useful introductory characterisation is provided by Georges Dreyfus, author of the pre-eminent book on Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism, who writes: ‘I believe the most distinctive feature of scholasticism to be its emphasis on interpreting the great texts constitutive of the tradition within the confines of its authority, using the intellectual tools handed down from previous generations.”[1]

Elaborating further, the first point to note is that scholasticism is concerned with a defined corpus of great texts. Interestingly, in Tibetan Buddhist contexts, these are not primarily the translated sūtras and tantras attributed to the Buddha himself, which are collected in the Kangyur, but the translated śāstras (‘treatises’) composed by Indian masters of the first millennium C.E. such as Nāgārjuna, Candrakīrti, Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, which are collected in the Tengyur. These, in turn, tend to be elucidated through commentaries composed by Tibetan authors, which often present the distinctive positions of Tibetan Buddhism’s major schools. Thus, for example, the commentaries of Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa (1357–1419) are widely studied in Geluk circles while those of Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429–1489) are used in Sakya circles.

The second point is that these great texts are not merely treated as objects of devotion but are subjected to systematic interpretation. The purpose of such interpretation is to resolve the seeming inconsistencies between different texts and to formulate the doctrinal positions contained within them in a way that is rationally coherent and defensible. In Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism, the inherited “intellectual tools” that provide the framework for valid reasoning are those of the Pramāṇa tradition, which originated with the Indian masters Dignāga and Dharmakīrti. The quintessential pedagogical and analytical method associated with this tradition is debate (rtsod pa), in which participants challenge or defend specific propositions according to precise logical rules. However, other important methods that play a prominent role in Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism include memorisation, oral commentary and, especially in the case of more advanced scholars, written composition.[2]

It should be emphasised that there are limits to the scope of approved interpretation. In Tibetan Buddhist scholastic communities, it goes unquestioned that the great texts were composed by individuals who had attained a high level of insight into the Buddha’s teachings. It is considered legitimate to dispute which exact philosophical standpoint an author upholds in a particular text, or to argue that the assertions of one author are lower in a doxography of Buddhist views than the assertions of another author. In fact, polemical exchanges between representatives of Tibetan Buddhism’s various schools sometimes hinge on precisely such disagreements.[3] However, it is not permitted to deny the truth or at least the pedagogical utility of the great texts outright; doing so is thought tantamount to declaring oneself a non-Buddhist. In Tibetan Buddhism, as in other religions, scholastic participants seek to reconcile reason and authority, and thereby attain deeper spiritual conviction, not to use one to defeat the other. Indeed, scholastic activities are often justified in Tibetan Buddhism on the grounds that they serve as a foundation for subsequent meditative practice and realisation, as epitomised in the ideal threefold process of studying, reflecting and meditating (thos bsam sgom).

That being said, the value of scholasticism has sometimes been contested in Tibetan contexts, for example by figures such as Karma Pakshi (1204–1283).[4] Common critiques contend that lengthy hair-splitting analysis can distract from more important soteriological tasks, that intellectual rivalry and achievement can give rise to afflictive emotions such as pride, and even that language itself – the medium of scholasticism – can be a hindrance rather than a help to the direct perception of reality.

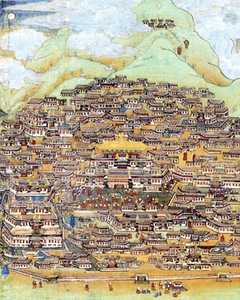

The history of Tibetan scholasticism is complex and only partially understood. Important landmarks include the early innovations at the monastery of Sangpu Neutok during the Second Dissemination (phyi dar); Sakya Paṇḍita’s (1182–1251) promotion of the Five Major Sciences (rig gnas chen po lnga) studied in classical India; the rise of the major Geluk ‘seats’ (gdan sa) of Ganden, Sera and Drepung from the fifteenth century, where Tibetan scholasticism attained its highest sophistication; and the widespread establishment of Nyingma, Kagyu and Sakya ‘commentarial colleges’ (bshad grwa) in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the present day, Tibetan Buddhist scholastic institutions continue to thrive not only inside Tibet but also in India, Nepal and Bhutan. A notable development in recent decades has been the establishment of scholastic programmes for nuns, who historically had few opportunities to receive this form of education.

References and Further Reading

Cabezón, J. I. 1998. ‘Introduction.’ In Scholasticism: Cross‐Cultural and Comparative Perspectives. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1–17.

Dreyfus, G. 2003. The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hobhouse, N.S. 2024. ‘Traditional Tibetan Buddhist Monastic Education and Its Contemporary Adaptations Since 1959.’ Religion Compass, 18:9, e70000. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.70000

Hugon, P. and B. Kellner. 2020. ‘Rethinking Scholastic Communities in Medieval Eurasia: Introduction.’ In Rethinking Scholastic Communities in Medieval Eurasia. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences, 2–11.

Kapstein, M. T. 2000. ‘Ch.6 What is “Tibetan Scholasticism”? Three Ways of Thought.’ In The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 85–120.

Schneider, N. 2022. ‘A Revolution in Red Robes: Tibetan Nuns Obtaining the Doctoral Degree in Buddhist Studies (Geshema).’ Religion, 13:9, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13090838

Yamamoto, C. S. 2009. The Historical Roots of Tibetan Scholasticism. Religion Compass 3:5, 823-835. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00170.x

Version: 1.0-20251219

-

Drefyus (2003:11) ↩

-

The triad of oral commentary, debate and written composition is encapsulated in the pithy Tibetan formula ’chad rtsod rtsom. It is notable, however, that writing is marginalised in traditional Geluk scholasticism. ↩

-

Even in these respects, however, the boundaries of legitimate interpretation are contested. For example, from the perspective of the Geluk school, the ‘other emptiness’ (gzhan stong) interpretation of the Jonang school lies beyond the pale of Buddhist orthodoxy. ↩

-

Kapstein (2000:97–106) ↩