Song of Dzogchen Instructions

Song of Dzogchen Instructions[1]

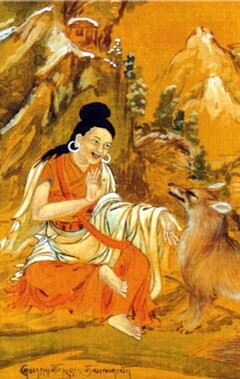

by Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol

I bow my head in homage at the feet of the Dharma King:[2]

Bless me that I might see natural luminosity.

Ema, child of great fortune!

Sit without moving your body,

Like a peg[3] driven into hard earth!

Sit with your eyes neither closed nor open too wide,

With the open gaze of a deity in a fresco!

And let your mind settle, loose and relaxed,

Like wool that is spread out upon the ground.[4]

While resting, once thoughts have ceased,

Mind becomes like a clear, cloudless sky,

As transparent as flawless crystal.

This itself is the view of the ultimate,

The luminous Great Perfection.

So rest in equipoise within that state.

This luminosity, which is clear like the sky,

Could not be mistaken for drowsiness or torpor.

But there is a great risk of confusing it

For clear, thought-free concentration,[5]

So do not allow yourself to go astray.

When thoughts arise, be they good or bad,

Don't chase after them, but turn within,

And look at them directly.

Allow your mind gently to relax.

Thoughts will be pacified right where they are.

When you settle in meditation for a long while,

Then, just like muddy water becoming clear,

So that various reflections appear within it,

Mind itself grows clearer and more vivid.

And many qualities effortlessly arise,

Such as enhanced vision and perception.[6]

Should even the Master of Oḍḍiyāna[7] appear before you,

He'd have nothing more to say on the view of the Great Perfection.

Should even Longchen Rabjam appear before you,

He’d have nothing to add about bringing thoughts onto the path.

Should even the twenty-five exalted disciples appear before you,

They’d have nothing more to say concerning this experience.

As for me, a yogin, even in sleep or moving about,

I have nothing more than this on which to meditate.

You might analyze meticulously, and then see

This clear and empty nature of mind,

Like seeing the sky when wind has dispersed the clouds,

But there is nothing greater than this to be seen.

Or you might settle naturally without analysis,

And see this clear and empty nature of mind,

Just as water becomes clear if you do not stir it.

But there is nothing greater than this to be seen.

Although there are many classifications of the view,

This clear, empty mind-as-such, devoid of grasping,

Is the unmistaken view of the Great Perfection.

When it is time for yogins of this method to die,

They will seize the clear light of death.

May hearing this prove beneficial,

And bring about the realization of clear light!

| Translated by Sean Price, Yeshi Chötso and Adam Pearcey, with many thanks to Tulku Yeshi Rinpoche, 2023.

Bibliography

Tibetan Edition

Zhabs dkar ba tshogs drug rang grol. "sa bcu'i dbang phyug rma chen spom ra'i gangs ri'i mgul nas bzhengs pa'i skor" In gsung 'bum tshogs drug rang grol. 15 vols. New Delhi: Shechen Publications, 2003. Vol. 4: 463–465

Secondary Sources

Khenpo Gangshar Wangpo. Songs of Realization and Pith Instructions. Halifax: Nalanda Translation Committee, 2022.

Tulku Yeshi Rinpoche, Concise Great Perfection Instructions of the Dzogchen Yogi Shbakar Tshokdruk Rangdrol. Heruka Institute, 2023.

Version: 1.3-20251215

-

A virtually identical text has been attributed to Khenpo Gangshar Wangpo (Gang shar dbang po. "rdzogs chen lta ba 'khrul med du ngo sprod pa'i mgur ma" in gsung 'bum/_gang shar dbang po. 1 vols. Kathmandu: Thrangu Tashi Choling, 2008, vol. 1: 99–101). However, it clearly derives from this song composed by the Dzogchen yogin Shabkar Tsokdruk Rangdrol (1781–1851). The original song is untitled; this title has been added by the translators based on comments by Tulku Yeshi Rinpoche. ↩

-

A reference to Chögyal Ngakgi Wangpo (chos rgyal ngag gi dbang po, 1736–1807), Shabkar's root teacher. ↩

-

The Tibetan word refers to a peg that is used to tether a baby yak to prevent it from approaching its mother, so that milk can be harvested from the mother. ↩

-

After shearing sheep, Tibetan nomads usually lay the wool flat on the ground, so that the smell and/or dampness may dissipate. ↩

-

The text is warning of the danger of mistaking thought-free concentration (dhyāna) for liberation and luminosity. ↩

-

This is a reference to the five types of clairvoyance or supernatural perception (pañcābhijñā; mgnon shes lnga) and the so-called five eyes (pañcacakṣu; spyan lnga), or five types of vision. ↩

-

i.e., Guru Padmasambhava. ↩