Introduction to Abecedarian Poetry

Introduction to Abecedarian Poetry

by Lowell Cook

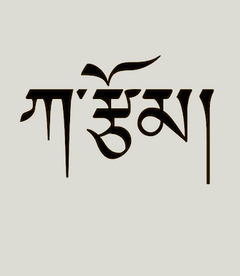

Abecedarian poems are a particular form of acrostic poetry in which each line is arranged around the alphabet. Known in the Tibetan literary tradition as ka rtsom, ka bshad, and, less often, ka phreng, abecedarian poems have historically been one of the most popular poetic forms in Tibet.

Tibetan abecedarian poems are almost always written in metered verse, although there are instances of poems written more freely and even oral versions. The letters of the Tibetan alphabet are most commonly placed at the beginning of each line of verse to form an acrostic, but they may also appear in the middle or at the end of a line. This alphabetical arrangement could be in forward (lugs ’byung) or reverse (lugs ldog) order, or even a mixture thereof (lugs ’byung lugs ldog zung ’brel) and, even more rarely, according to the letters’ genders. Abecedarian poems may also be combined with other poetic forms like fixed vowels (dbyangs yig nges pa) in which only one of the four Tibetan vowel signs is used—or else they are all omitted, leaving only the signless vowel a—throughout an entire line or stanza. The possibility of combining these various features means that there are virtually countless forms in which Tibetan abecedarian poems might be written.

The origins of abecedarian poetry in Tibet are somewhat anomalous. Abecedarian poems had a minor presence in Indian Buddhist literature,[1] and a few are preserved in the Kangyur and Tengyur.[2] The abecedarian form, however, is not part of Daṇḍin’s Mirror of Poetics (Kāvyādarśa) which became the definitive treatise on poetic theory for Tibetans. While some scholars have attempted to locate abecedarian poetry in the Mirror of Poetics’ third chapter on “sound ornaments” (Skt. śabdālaṅkāra, Tib. sgra rgyan), abecedarian poetry and sound ornaments differ from each other in significant ways.[3] It is thus clear that, while Tibetans did not directly appropriate their abecedarian form from any single Indic work or body of works, abecedarian poetry in Tibet did not develop in complete isolation. In his essay on the origins of abecedarian poetry in Tibet, Rasé Könchok Gyatso (the name under which Drikung Chenga Rinpoché writes) similarly concludes that this form emerged in a literary environment in which poetic exploration was thriving thanks to the then recently translated Mirror of Poetics[4] and through the combination of the Tibetan authors’ grounding in traditional songs (gna’ bo’i mgur glu) and the inspiration afforded by newly translated Indian writings.[5]

There are no Tibetan abecedarian poems that date to the Imperial Period (bstan po’i skabs, 618–842). During the Period of Fragmentation (sil bu’i dus, c. 900–1250), we see the first proto-abecedarian poem in a stanza from Ngok Lotsawa Loden Sherab’s (1059–1109) grammar treatise A Primer of Essential Orthography (dag yig nyer mkho bsdus pa). This stanza includes all thirty consonants of the Tibetan alphabet, although not in acrostic form. As such, it should technically be designated as a pangram rather than an abecedarian poem proper.[6] In 1260, Drogön Chögyal Phakpa Lodrö Gyaltsen (1235–1280) wrote the first full-fledged abecedarian poem, Illuminating the Great Vehicle: A Poem Written Based on the Matrix of Letters,[7] in addition to An Alphabet Poem.[8] The fourteenth century would see a flourishing of such poems with, most notably, the 10th Drikung throne-holder Dorje Gyalpo (1283/1284–1350/1351), Longchen Rabjam Drimé Özer (1308–1364),[9] and Tsongkhapa Lobzang Drakpa (1357–1419), among others, writing in abecedarian form. From there, abecedarian poetry continued to be written in increasingly creative and complex manners, becoming a particularly cherished form for Buddhist masters and scholars alike to display their poetic prowess.

Translators of Tibetan abecedarian poems into English have increasingly attempted to reproduce the abecedarian form of their sources via the English alphabet. While prioritizing the form (brjod byed tshig) typically necessitates a certain degree of poetic license with the content (brjod bya don), there have been some remarkably successful translations.[10]

Bibliography & Further Reading

84000. The Play in Full (Lalitavistara, rgya cher rol pa, Toh 95). Translated by Dharmachakra Translation Committee. Online publication. 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha, 2025. https://84000.co/translation/toh95.

84000. The Alphabet Dohā (Kakhasyadohā, Toh 2266). Translated by the Subashita Translation Team. Online publication. 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha, forthcoming.

Blum, Mark Laurence. The Nirvana Sutra (Mahāparinirvāṇa-Sūtra). Vol. 1. Berkeley: BDK America. 2013, p. 253.

Bu chung thar. “ka rtsom dang snyan ngag me long las bstan pa’i sgra rgyan gyi khad par brjod pa.” In Bod ljongs zhib ’jug. Issue 2, 1995.

Chab spel tshe brtan phun tshogs. “Ka bshad rtsom rig skor cung zad gleng ba.” In Bod kyi rtsom rig sgyu rtsal. Issue 1, 1983.

Harding, Sarah. Pha Dampa Sangye and the Alphabet Goddess: A preliminary study of the sources of the Zhije tradition. Presented by Sarah Harding at the 2016 meeting of the International Association of Tibetan Studies (IATS) in Bergen, Norway. https://www.tsadra.org/2016/07/13/pha-dampa-sangye-and-the-alphabet-goddess

Martin, Dan. “Devotional, Covenantal and Yogic: Three Episodes in the Religious Use of Alphabet and Letter From a Millenium of Great Vehicle Buddhism”. in The Poetics of Grammar and the Metaphysics of Sound and Sign ed. S. LaPorta and D. Shulman. Leiden: Brill, 2007. pp. 201-233.

Melzer, Gudrun. An Acrostic Poem Based on the Arapacana Alphabet from Gandhāra: Bajaur Collection Kharoṣṭhī Fragment 5. (2018; updated July 2020)

Mig dmar tshe ring. “Ka bshad rtsom lugs kyi skor.” In Mig dmar tshe ring gi rtsom yig thor bu phyogs bsgrigs. Beijing: Krung go’i bod rig pa dpe skrun khang. Volume 1. 2005.

Ngok Lotsāwa Loden Sherab. “Dag yig nyer mkho bsdus pa.” In bKaʼ gdams gsung ʼbum phyogs bsgrigs thengs dang po, Par gzhi dang po., 1:97–114. 1 (1-30). Khreng tuʼu: Si khron dpe skrun tshogs pa si khron mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2006.

Rta mgrin skyabs. Ka rtsom gyi byung ’phel dang de’i sgyu rtsal khyad chos la dpyad pa (Research on Development of ka-Rtsom and its Characteristics). MA Thesis, Northwest University for Nationalities, 2014.

Ra se dkon mchog rgya mtsho. “Bod kyi ka bshad kyi rtsom lus kyi thog ma’i’byung khung gang yin nam.” In Bod rig pa’i dpyad rtsom brgya dang brgyad cu ma. Private publication with permission from Bod rang skyong ljongs dpe skrun do dam khru’u.

Ricard, Matthieu. The Life of Shabkar: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Yogi. New York: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Saraha. “ka kha'i do hA/.” In bstan 'gyur (dpe bsdur ma). Vol. 26: 1150-1156. bai ro tsa na badz+ra, trans. Beijing: krung go'i bod rig pa'i dpe skrun khang, 1994-2008.

______. “ka kha'i do ha'i bshad pa bris pa/.” In bstan 'gyur (dpe bsdur ma). Vol. 26: 1157-1179. bai ro tsa na badz+ra, trans. Beijing: krung go'i bod rig pa'i dpe skrun khang, 1994-2008.

Smyug rtse. “Bod kyi ka rtsom gyi rigs dang lus kyi dbye tshul la thog mar dpyad pa.” In Bod ljongs zhib ’jug. Issue 1, 1994.

Townsend, Dominique. "On Gutsiness: The Courageous Eloquence of Pöpa Chenpo" in Holly Gayley and Andrew Quintman (ed.) Living Treasure: Buddhist and Tibetan Studies in Honor of Janet Gyatso, Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications, 2023: 177–191.

Version: 1.0-20250904

-

One of the oldest Buddhist manuscripts discovered is fragment 5 of the Bajaur Collection (known as BC 5), a Gandhāri abecedarian hymn of praise dated to the first or second century CE that employs an acrostic of the Arapacana syllabary. See Melzer (2020) for more on this text. ↩

-

In the Kangyur, examples of abecedarian poems include lines 10.16–23 from Chapter 10 “The Demonstration at the Writing School” of The Play in Full (Toh 95, lalitavistara, rgya cher rol pa), the “Garland of Letters Section” from the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra (Toh 119, 大般涅槃經, ’phags pa yongs su mya ngan las ’das pa chen po’i mdo), and The King of Desire (Toh 405, rāgarājatantra, chags pa’i rgyal po’i rgyud). In the Tengyur, the main work that employs an abecedarian form is Saraha’s Alphabet Dohā (Toh 2266, kakhasyadohā). There are other works in the Tengyur that focus on the role of the Sanskrit alphabet in tantric meditations but which do not employ the alphabet as a literary device. These include Ghaṇṭa’s A Classification of Mantras in Terms of Vowels and Consonants (Toh 2404, ālikālimantrajñāna, a phreng ka phreng gi sngags kyi rim pa), Dhamadhuma’s The Path of Meditating on a Garland of Syllables (Toh 2405, kālibhāvanāmārga, ka phreng sgom pa’i lam), and Sāgara’s The Mahāyoga Meditation on Cakrasamvara with Vowels and Consonants (Toh 2406, śamvaracakreśvarālikālimahāyogabhāvanā, a phreng ka phreng bde mchog ’khor lo’i rnal ’byor chen po bsgom pa). ↩

-

For the specific differences between ka rtsom and sgra rgyan, see Bu chung thar (1995) and Rta mgrin skyabs (2014). ↩

-

During the 13th century, we see the first partial translation of the Mirror of Poetics by Sakya Paṇḍita (1182–1251) and the first full translation by Shongtön Dorje Gyaltsen (early 13th–late 13th C.), which brought about a flourishing of new literary exploration and creativity. ↩

-

Ra se dkon mchog rgya mtsho, p. 790. ↩

-

This, however, is where we see the breakdown of translating Tibetan literary concepts into English and vice versa, since a number of Tibetan scholars, such as Bu chung thar (1995) p. 55, Pema Bhum (personal correspondence), and others, do consider this stanza to be the first Tibetan abecedarian poem. ↩

-

Theg chen gsal ba’i yi ge ma mo spel ba’i rab byed. ↩

-

Ka sogs sum cu la spel ba. ↩

-

See Disheartened by Circumstances: An Abecedarian Poem (rkyen la khams ’dus pa ka kha sum cu). ↩

-

Some successful attempts at recreating Tibetan abecedarian poems in English include "A Celebration of Shabkar: The Melody of Pure Devotion" by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Ricard, The Life of Shabkar: The Autobiography of A Tibetan Yogi, pp. xxxi–xxxii; Dominique Townsend's translation of Terdak Lingpa's "An Abecedarian Song of Courageous Eloquence" in Townsend, "On Gutsiness: The Courageous Eloquence of Pöpa Chenpo"; and Advice in Abecedarian Form by Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö and The Wish-Fulfilling Jeweled Lute: Praises to Kyechok Tsulzang by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche on the present site. ↩