Introduction to Gaṇacakra (Tsok)

Introduction to Gaṇacakra

by Stefan Mang

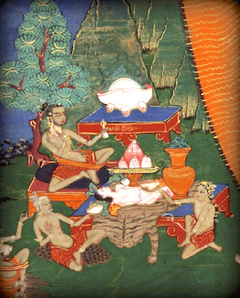

Gaṇacakra (tshogs kyi 'khor lo) is a ritualized feast in which the deities of a specific tantric system are worshipped as part of a group practice.[1] Gaṇacakra creates a particular kind of maṇḍala, or ‘sacred ritual space’, for the practices of many higher tantras (mahā, anu- and ati-yoga, or niruttarayoga).[2] Gaṇacakra is an important milestone in the development of the internalization of tantric practices and the formation of group practice. The main goals of performing a gaṇacakra are to gather the accumulations of merit and wisdom (puṇya- and jñāna-saṃbhāra; bsod nams and ye shes kyi tshogs) and to maintain and restore the commitments (samaya; dam tshig) made at the time of receiving empowerment or initiation (abhiṣeka; dbang) into the higher tantras.[3] Since its introduction in the ~9th century,[4] gaṇacakra gained great popularity, and it is practiced nowadays by many followers of Tibetan Buddhism on a regular basis.

Gaṇacakra is structured around several key elements that are consistent throughout the Indian and Tibetan traditions. We find gaṇacakra commentaries in both traditions that do not affiliate themselves with any specific tantric cycle, but rather aim to be as general as possible in order to be applicable to any instance of practice.[5] While there remains a certain degree of variation amongst gaṇacakra rituals depending upon the sādhana, the ritual tradition, and the time of its composition, the following key elements consistently appear:[6] gaṇacakra requires a specially prepared ritual place and a group of participants that include a ritual master, practitioners, both male and female, and ritual-assistant(s). Together these form the maṇḍala of the samaya beings (samayasattvas; dam tshig pa), that is, the assembly of deities visualized by the participants. The ritual is performed on specific days of the lunar cycle, in a sacred place or a specially prepared shrine. Non-initiates and those with broken samayas are prohibited from participating. The participants set up the ritual space and prepare the offering. The participants then invite the wisdom beings (jñānasattvas; ye shes pa), that is, the ‘actual’ deities, and through this the offerings are blessed and transformed into samaya substances. These substances are then offered to the deities and also consumed by the participants. This is accompanied by further rituals and practices, such as song and dance. Offerings are also made to worldly deities to satisfy and appease them and in order to invoke their protection. Finally, the visualization of the maṇḍala is dissolved and the jñānasattvas are requested to depart. The ritual is usually concluded by making prayers of aspiration and dedicating the merit for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Gaṇacakra was likely introduced into Buddhism by the “proto-yoginītantra”, the Sarvabuddhasamāyoga, wherein it is referred to as gaṇamaṇḍala, in the ~9th century.[7] In the later yoginītantras which appear after the ~9th century, such as the Catuṣpīṭha, Cakrasaṃvara, Hevajra and Kālacakra, gaṇacakra features with increasing prominence. The original sources for gaṇacakra are thus the yoginītantras as well as their Indian commentaries that have been preserved in Sanskrit and Tibetan. In addition to these tantras and their commentaries, sixteen stand-alone gaṇacakra ritual manuals (gaṇavidhis), which provide detailed instructions on the actual performance of gaṇacakra, have been preserved in Tibetan.[8] The Sarma (gsar ma) schools of Tibetan Buddhism take the above-mentioned scriptures now available in the Kangyur (bka’ ’gyur) and Tengyur (bstan ’gyur) as primary sources for their explanation of gaṇacakra and regularly cite them in their commentaries on the practice. One of the most important Sarma school gaṇacakra commentaries is Sakya Paṇḍita's (1182-1251) The Gaṇacakra Ritual (tshogs 'khor cho ga). The Nyingma (rnying ma) School, by contrast, tends to base its explanations on certain Nyingma-specific scriptures now present in the canon of the Nyingma School, collectively referred to as the Nyingma Gyübum (rnying ma rgyud ’bum).[9] Amongst them, the Essence of Secrets Tantra (Guhyagarbha; gsang ba’i snying po) and Pal Heruka Galpo (dpal he ru ka gal po) in particular are frequently cited sources. One of the most important Nyingma presentations of gaṇacakra is to be found in Jigme Lingpa's (1730–1798) Detailed Commentary on the Lama Gongdü (dgongs 'dus rnam bshad). Following a standardization of the ritual structure during the 18th and 19th centuries, several Nyingma authors have composed shorter, more 'generic' commentaries on the practice,[10] such as those by Tsele Natsok Rangdrol (b. 1608), Adzom Gyalse (1895–1969) and Gönpo Tseten (1906–1991), which are applicable to any practice of gaṇacakra.

Further Reading

Cantwell, Catherine. "To Meditate upon Consciousness as vajra: Ritual ‘Killing and Liberation’in the rNying-ma-pa Tradition." In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Seventh Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies (1995), Graz: 107–118.

Collet-Cassart, Benjamin. “The Generic Commentaries on Development Stage in the 18th and 19th Centuries A.D. A Study and Translation of Kunkhyen Tenpe Nyima’s ‘Compendium of Key Instructions’.” Unpublished MA Dissertation. Kathmandu: Rangjung Yeshe Institute, 2011.

Dalton, Jacob. "A Crisis of Doxography: How Tibetans Organized Tantra during the 8th–12th Centuries." Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (2005): 115–181.

Haruki, Shizuka. “An Interim Report on the Study of Gaṇacakra: Vajrayāna’s New Horizon in Indian Buddhism.” In Editorial Board, ICEBS, Esoteric Buddhist Studies: Identity in Diversity: 185–198. Koyasan: Koyasan University, 2008.

Sugiki, Tsunehiko. "The Consumption of Food as a Practice of Fire-oblation." In Esoteric Buddhism in Medieval South Asia: 53–79. International Journal of South Asian Studies, 3, 2010.

Szántó, Péter-Dániel. "Minor Vajrayāna texts V: The Gaṇacakravidhi attributed to Ratnākaraśānti." Tantric Communities in Context (2019): 275-314.

Szántó, Péter-Dániel & Arlo Griffiths. "Sarvabuddhasamāyogaḍākinījālaśaṃvara". In Brill Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Vol. I Literature and Languages, ed. Oskar Von Hinuber, Vincent Eltschinger, and Jonathan Silk, 365-372. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Version: 1.1-20250226

-

Szántó & Griffiths 2015, 367. ↩

-

Shizuka 2008, pp. 187–188. The classification of tantras into mahā, anu- and ati-yoga reflects the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism; the Sarma schools consider these three as stages of a single vehicle of niruttarayoga tantras. See: Dalton 2005, 141. ↩

-

Szántó 2019. ↩

-

It is, of course, very difficult to determine when the practice of gaṇacakra first arose. The date provided here is provisional and intended merely to offer a rough historical orientation. ↩

-

For an Indian example of such a general commentary, see: Szántó 2019. For a Tibetan example, see the gaṇacakra commentary by Adzom Gyalse. ↩

-

See also Szántó's presentation of the main points of an Indian gaṇacakra in: Szántó 2019. ↩

-

Szántó & Griffiths 2015, 368 & 340; and Shizuka 2008, 188. ↩

-

Only one of these sixteen manuscript is still available in Sanskrit and was found and discussed by Péter-Dániel Szántó (Szántó 2019). ↩

-

In comparison to the tantras and commentaries in the Kangyur and Tengyur collections, gaṇacakra as presented in the Nyingma tantras (rnying rgyud) reveals several unique ritual features. ↩

-

Collet-Cassart 2011, iv-2. ↩