Introduction to Siṃhamukhā

Introduction to Siṃhamukhā

by Stefan Mang

Siṃhamukhā,[1] known in Tibetan as Senge Dongma (seng ge gdong ma)—literally “lion-faced”—is a fierce female deity in the Vajrayāna Buddhist tradition. Commonly classified as a ḍākinī or yoginī within the Highest Yoga Tantra (Yoga-niruttara) systems, she appears in several Indian and Tibetan tantric cycles and is particularly associated with the Guhyasamāja and Cakrasaṃvara tantras. Siṃhamukhā is invoked as a powerful protector, renowned for swiftly removing obstacles, reversing curses and magical attacks, and dispelling harm and obstructive forces. More than a guardian spirit, she is revered as a fully enlightened ḍākinī—an embodiment of awakened wisdom in wrathful form—who not only wards off external threats but also vanquishes the inner enemies of delusive thought and obscurations to awakening. Accordingly, sādhanas dedicated to her serve not merely as protective rites, but as complete paths leading the practitioner toward full realization.[2]

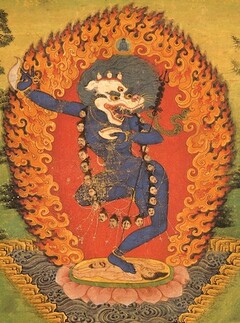

Though iconographic details vary across lineages, Siṃhamukhā is typically portrayed—as her name implies—with the head of a roaring lion. Her body, usually blue or red, is encircled by flames of pristine awareness. She stands in a dynamic, dancing posture, adorned with bone ornaments and a tiger-skin skirt, brandishing a curved flaying knife and a skull-cup, while cradling a khaṭvāṅga staff against her shoulder.[3]

According to the Nyingma (rnying ma) school, Siṃhamukhā’s practice was revealed and later transmitted to Tibet through Guru Padmasambhava and preserved in the treasure literature (gter ma). As recounted in his biographical accounts, when black magicians threatened Bodh Gaya and the monastic university of Nālandā, Guru Padmasambhava was summoned to protect the Dharma. In response, he meditated on Siṃhamukhā,[4] who appeared and bestowed upon him her practice and mantra. Empowered by her blessings, he assumed his wrathful form, Guru Sengé Dradok (Tib. gu ru seng ge sgra sgrogs), and subdued the hostile forces.[5] For this reason, Siṃhamukhā is often regarded as a secret or inner manifestation of Guru Padmasambhava in ḍākinī form.

In the Sakya (sa skya) tradition, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820–1892) traces Siṃhamukhā’s lineage in a historical account that serves as the introduction to his collection of orally (bka’ ma) transmitted practices entitled The Excellent Vase of Precious Jewels (rin chen bum bzang). The lineage begins with the 11th-century translator Bari Lotsawa, who received her practice after becoming the target of black magic. Following the guidance of the yogi Chiterwa in Nepal, he traveled to India, where the master Vajrāsana initiated him into tantric rites. During his practice, Simhamukhā appeared in a visionary maṇḍala and revealed her fourteen-syllable mantra. Through daily recitation, Baripa neutralized the magical attack and later transmitted the practice to Sachen Kunga Nyingpo, thereby securing its place within the Sakya tradition.

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo further recounts that the transmission eventually reached the yogi Namkha Sangye Gönpo, who, afflicted with leprosy, encountered Siṃhamukhā in a vision. She healed him and directly transmitted her teachings, which he passed on to Repa Kunga Darpo. The lineage was preserved through figures such as Tsöndru Senge and Chökyi Nyima—Khyentse Wangpo’s own teacher—thus ensuring the continuity of this esoteric and potent transmission.

Further Reading

Jamgön Kongtrul. The Life and Liberation of Padmakara, the Second Buddha. Trans. Trans. Samye Translations, Lotsawa House, 2018.

Jamyang Khyentsé Wangpo. History of Siṃhamukhā Practice. Trans. Samye Translations, Lotsawa House.

Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoché and Khenpo Tsewang. Liberating Duality with Wisdom Display: Eight Emanations of Guru Padmasambhava. Sidney: Dharma Samudra, 2012.

Shaw, Miranda. Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Version: 1.0-20250711

-

Also known as Siṃhamukhī. The names Siṃhinī, Siṃhavaktrā, and Siṃhāsyā appear to be used primarily for attendant figures or non-Buddhist deities. ↩

-

Shaw 2006, 424–425. ↩

-

Shaw 2006, 424–425. ↩

-

In these accounts Siṃhamukhā may also be referred to as Mārajitā, Tamer of Māras. ↩

-

Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoché and Khenpo Tsewang 2012, 75–80. And: Jamgön Kontrul 2018. ↩